254 shades of gray – Ingrid’s beautiful logic legacy

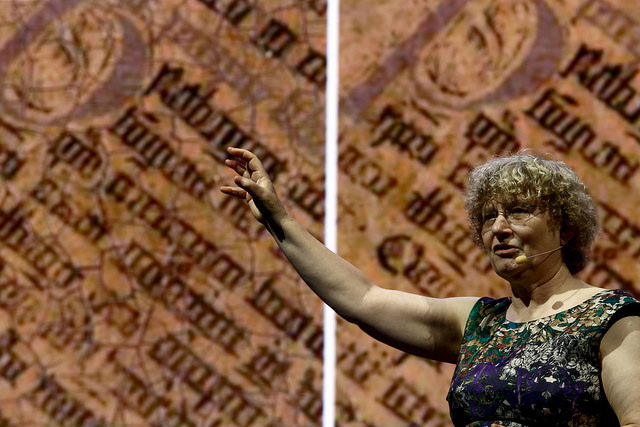

If one of the greatest pleasures in life is the feeling of really helping others, Ingrid Daubechies must be one of the happiest people at the ICM 2018. Her work in pure mathematics has been applied to various fields including image compression, data storage, paleontology and also in the restoration of classic works of art.

Ingrid studied physics in Brussels before marrying American mathematician, Robert Calderbank, whom she met when he was on a three-month exchange from AT&T Bell Laboratories in New Jersey, USA. After moving to the States, Ingrid started making significant discoveries in the field of wavelets, studying mathematical structures perceived as kinds of waves. She discovered there are various types of wavelets, the characteristics of which she was able to describe in her, now classic, 1992 publication: Ten Lectures on Wavelets.

Read more: ‘Le Magicien’ brings snow to Brazil through math

Montanari method: Mixing physics, stats & math

Leelavati Prize winner creates new learning paradigms in Turkey

Always keen that her work is used outside the field of pure mathematics, Daubechies’ breakthrough was used in the creation of JPEG2000 standard, the format for storing digital images. Her specific mathematical formulae enable the data to be compressed and stored much more efficiently. All our selfies and holiday snaps can now be stored and sent online much more easily thanks to Ingrid’s work. Previously, the FBI was one of the first to utilize the new technology in streamlining the storage of fingerprint data.

It was her achievements in the world of art history that the former President of the IMU (2011-2014) came to talk about at this year’s second public lecture. She presented stunning examples of how her work in image analysis has been used to restore, rejuvenate and uncover lost works.

First, she explained how, along with Massimo Fornasier, she was able to restore entire frescos from a church in Padua, Italy – heavily bombed during the Second World War.

After the war was over, local art historians and conservators were faced with the daunting task of trying to piece together over 80,000 fragments of painted stone, which formerly covered over 800 square meters of an interior wall inside the church. It was a seemingly impossible task. The pieces had lain in storage for decades, and teams had almost given up hope of reconstructing the work as only around 2% of the originals remained. The rest was reduced to rubble.

Upon being presented with the problem, Ingrid was able to use one of her favorite phrases: ‘Math can help!’ In the 90s, the pieces had been digitized and stored on computers, but at the time neither the computing power nor the techniques were available to get to grips with the project.

Using a record of black and white photographs, Ingrid and her team set about digitizing the images of the original frescos into hued pixels from brilliant white “0” to jet black “255”. Ingrid boasts that some people have ‘50 Shades of Gray,’ but her digital analysis has 254.

They then used a process of circular harmonics to work out the orientation of the fallen pieces, find matches and digitally map them onto the existing black and white photos. The complete color originals were then propagated from the fragments.

Another use of this incredible technology has been to recreate missing works. The Ghissi altarpiece which tells the story of John the Evangelist, painted in the 14th century, was removed from its home in Italy and the various panels sawn apart. They eventually found their way to various museums and collections, thankfully all in the same country, the USA. Curators wanted to bring together the nine panels of this great religiously-inspired masterpiece, but somewhere along the line, the final scene had gone missing.

Ingrid, along with Belgian artist, Charlotte Caspers, started to work on recreating the lost panel. They found the story of John the Evangelist in medieval ‘best-seller’ – Golden Legend – which gave them the scene to paint. Charlotte took the stylistic elements from the other panels and with painstaking detail, produced a faithful reconstruction. It was perfect. The problem now though, was that the new panel was so vivid that it didn’t fit with the other original pieces.

Once again, Ingrid told them ‘mathematics can help.’

Looking at the other panels to analyze the colors and using Ingrid’s mathematical technology the new image was digitally-aged to fit in. But now the team realized they could reverse the process and restore the original to its former brilliant glory.

The final exhibition contained the original with the digitally-aged recreation of the missing panel, a restored print of the altarpiece how it would have looked 600 years ago and a digital video demonstrating the glory of the original with its reflective gold leaf paint and ornate patterns. The perfect marriage of math and art – a collision of beauty and logic.